Date/Time

Date(s) - 03/24/2023 - 05/04/2023

12:00 am

Location

Buffalo Arts Studio

Categories

Opening Reception, Friday, March 24, 2023, 5:00—8:00 pm

Part of M&T Bank 4th Friday @ Tri-Main Center

Each year Buffalo Arts Studio invites up to three artists to participate in our artist-in-residence program. Our residencies support regional, national, and international artists with a focus on artists whose work is not only a powerful visual statement, but also spurs dialogue between varied audiences and open doors to social, economic, and environmental justice.

Artists-in-residence are selected based on the way(s) their practice fits within the Buffalo Arts Studio curatorial vision as well as their relevance to the larger exhibitions, panel discussions, and workshops. For the 2022/23 exhibition series Displacement: Reclaiming Place, Space, and Memory Artist-in-Residence, curator Shirley Verrico selected Sa’dia Rehman, a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores the structure of the family and the nation, as well as the borders around and between each. Rehman questions how we live within these systems and how these systems impact who we are, while also giving rise to the desire to rearrange, reimagine, and even dismantle them. Rehman centers familial history to expand on harm and survival, situating their own family history in the context of larger historical processes. Rehman also draws on traditions of Islamic art and architecture, as well as the modern art of Asian and African diasporas. As a result, Rehman’s artwork engages the relationship between structures, images, and memory in both the public and private sphere, examining how each relates, communicates, consolidates, and contests ideas about displacement and migration.

Mapping Ghosts

Curatorial Essay by Shirley Verrico

The Falls is an exhibition of new work by Sa’dia Rehman (they, them), a multidisciplinary artist who was artist-in-residence for ten days as part of the 2022/23 exhibition series Displacement: Reclaiming Place, Space, and Memory. All of the work in The Falls is rooted in Rehman’s research of their family’s 1974 displacement from their village Khar Kot, in Pakistan due to the building of the Tarbela Dam on the Indus River. Rehman centers familial history to expand on harm and survival, situating their own experience in the context of larger historical processes. Rehman also draws on traditions of Islamic art and architecture, examining the relationship between structures, images, and memory in both the public and private sphere, and considering how each relates, communicates, consolidates, and contests ideas about displacement and migration.

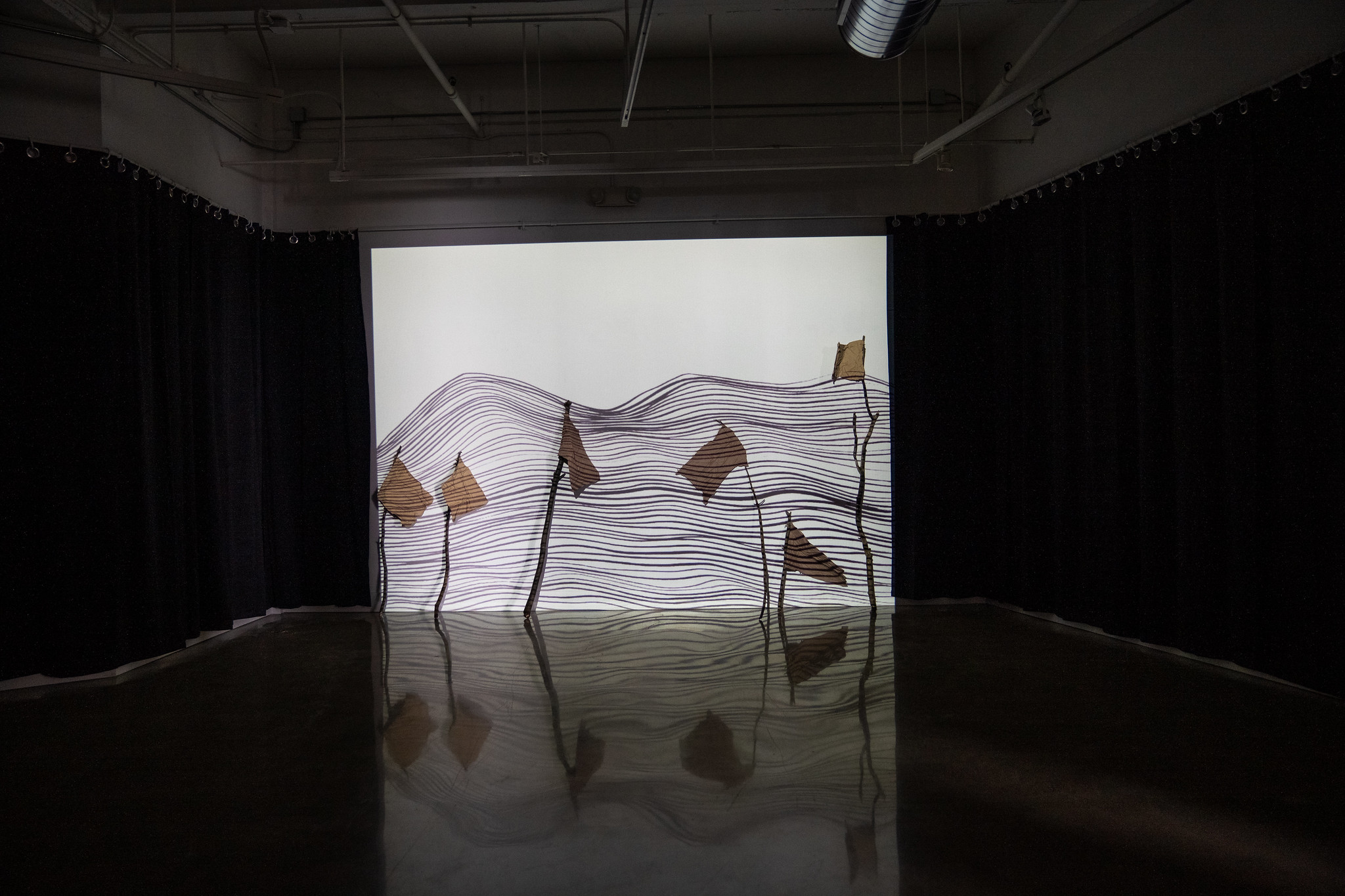

Rehman visited the Tarbela Dam and the Indus River with family in March 2022. In direct response to this experience, Rehman created Flags Submerged (2023, time-lapse video, mixed media) and To Witness (2022, plaster, evaporated water, glass fish tank).

“I am evoking that feeling of being on the reservoir and at the Dam. I saw that the water was thick, mixed with silt and clay and these large canoe-like boats moved as if we were gliding through piles of wet graphite. We rode along the Indus for an hour. There were sticks poking from the water- these were tops of trees, ghosts of trees, bare bone. I could see layers of sand, silt, dead plants, and animals and skeletons surrounding us in the sedimentary rock formations. I could see the many lines marking how high the water could reach.”

The time-lapse video consists of over 60 meditative drawings using brushed ink on paper, all made during Rehman’s residency at Buffalo Arts Studio. The lines rise and fall, pulsing with the rhythm of the time-lapse process. The video plays over unfired clay flags also made on-site with Buffalo terracotta and branches collected in Western New York. On the other side of the gallery, an empty tank holds a plaster cast of the artist’s hand pointing upwards towards the sky. In the last year, Rehman filled the tank with water, submerging all but the tip of a single finger of the plaster hand. As the water evaporated, the surfaces were marked by the residual elements left behind and another ecosystem began to grow on the plaster hand.

During their residency, Rehman also created Remnants, a 105 x 275 inch wall drawing using chalkboard paint, chalk, and sumi ink. The chalkboard paint suggests domestic and family spaces as it has become a popular part of home decor. Dominating the composition is a group of faceless figures drawn from a photo of Rehman’s extended family a year after they were shifted from the Indus to arid land southeast of the river. Rehman has compressed the time between the displacement in the early 1970s and Rehman’s own visit in 2022 by placing the figures atop the water and alongside the motor boat used to traverse the reservoir. The compositional space of the drawing is also compressed, with images fragmented and layered with stenciled patterns taken from the 15th century Ottoman volume titled The Album of the Conqueror. Rehman used sumi ink for the stencils, relying on the material’s reflective quality to activate the surface. Rehman also includes gestural drawings of mango trees, one of the crops decimated by the flooding caused by the dam. The Tarbela Dam project put 184 villages below water. It permanently displaced more than 100,000 people, including Rehman’s grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins. In the wintertime, when the water levels are low, one can still see relics of mosques, shrines, and cemeteries. The white drawings on the black background feel like ghosts and the media amplifies the temporality of the drawing made directly on the wall. The white chalk, which has been intentionally smeared by Rehman themself, can and will be easily erased. Hovering over the scene is a swirling disc, suggesting the sun and moon as well as the cyclical nature of colonial extraction and exploitation. Rehman notes that like many dam projects in the Global South, the Tarbela Dam was funded by the World Bank. Canadian, Italian, French, British, and American engineers, architects, and designers moved to Pakistan in the 1970s to oversee the $500 million US project. Debt accrued from these large infrastructure projects continues to negatively impact countries like Pakistan that are crippled by the high-risk debt distress.

As Remnants compresses time and space, several other works in the exhibition draw a stark dividing line. The top half of Rehman’s only untitled work (Untitled, 2022, India ink and clay on wood panel) contrasts the subtle vertical grain of wood, visible through the India ink, with the broken surface of unfired clay applied in long, horizontal strokes. Rehman intentionally did not prime or treat the panel in any way. As a result, the clay cracks and even flakes off the panel, revealing areas of ink marred by clay residue. In Mountain of Light (2022, sumi ink and rust on stretched linen) the divide between materials is organic, the result of Rehman laying bits of steel wool across part of the canvas and spraying water onto the surface to promote rusting. Rehman let the rust happen naturally, regularly tending to the canvas and rewetting as needed. The shape that emerged reminded Rehman of Jabal an-Nour, the ‘Mountain of the Light’ near Mecca where Muslims believe the Islamic prophet Muhammad spent time meditating, and where Muslims believe Muhammad received his first revelation. Rehman chose the reflective sumi ink for the black surface in Mountain of Light, allowing some of the ink to drip down into the rusted canvas. The surfaces of Mountain of Light are rich and seductive, imploring the viewer to engage with the active surface. Together, Mountain of Light and the untitled work form a call and response, dividing land and sky, science and spirituality.

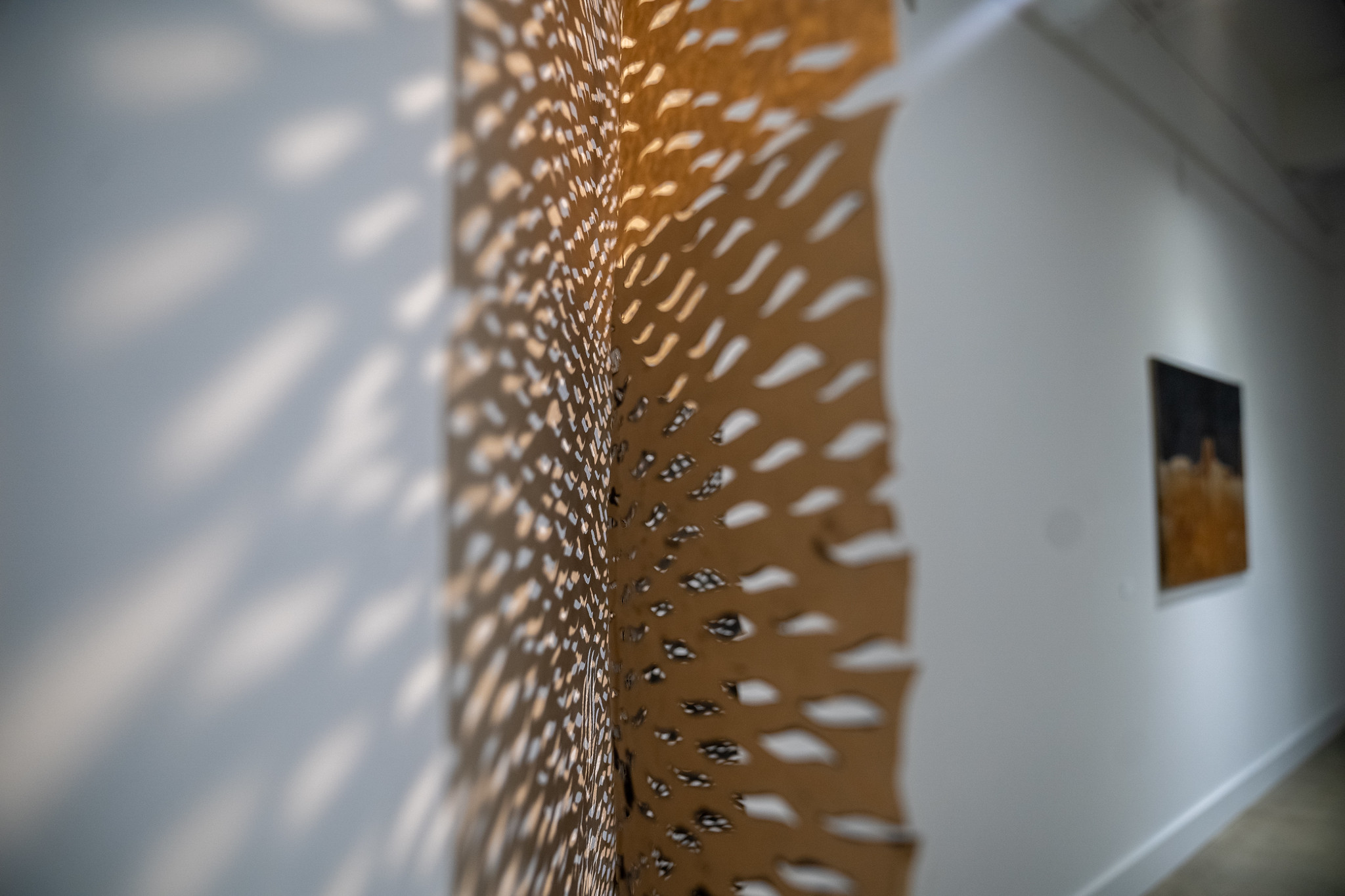

Waves, a tall vertical piece, is also divided. For Waves, (2022, cut brown paper bags, glue, and India Ink) Rehman collected dozens of paper bags, splaying each open and then gluing them together into a 100 inch long and 46 inch wide single sheet of paper. Rehman used a repetitive, gestural process to cut into the bags and create wave shapes that suggest both fire and water. Rehman made all cuts in one sitting and the repetition became ritualistic, a meditative process of action and reaction. Rehman then covered a little less than half of Waves with India ink to achieve the matte black surface that covers the lower part of the three dimensional piece. Although Waves is hung directly against the wall, the paper is no longer flat and the work pulses, albeit slowly in reaction to any movement within the gallery. The light shining on and through the cuts creates a slow shimmering, like sunlight reflecting on water or streaming through a leaf canopy. Waves refers back to Remnants, with Rehman using the same gesture to create the rhythm of moving water in both works. There is also a ghost image in Waves, created by the shadows on the wall behind the work rather than on the artwork itself.

The installation ends with ten Jupiter Moon drawings. Rehman used a single, hand-cut stencil to make all the circles in the Jupiter Moon series. Rehman brushed, rubbed, painted, and smudged ink, clay, graphite, earth, and rust through the stencil multiple times, pointing to some of the many resources extracted from Pakistan and South Asia. Rehman uses the stencil as both tool and object, relying on the imperfect nature of the border between the materials and the surface of the paper to produce variations and amplify imperfection. For some of the drawings, like Jupiter Moon 8 (2022, blue carbon on Arches paper) and Jupiter Moon 4 (2022, graphite on Arches paper), Rehman worked over and across the stencil, making disciplined marks by hand. In others, such as Jupiter Moon 3, Jupiter Moon 7, Jupiter Moon 9, and Jupiter Moon 10 (2022, rust on Arches paper), Rehman relied on time and chemistry to produce the rusted material passed through the stencil. As with Mountain of Light, Rehman had to tend to the process, wetting and rewetting the steel screws, rebar, and wool until enough rust appeared to meet the borders of the stencil. These repetitive acts constitute a conceptual practice evoking the circular and iterative relationships between history, memory, storytelling, and the self.

Khar Kot does not appear on 21st century maps of the region. The village was drowned long before satellite imagery became widely available. Google Maps places its red pin location marker over the reservoir while the website Places in the World lists the status as “destroyed place.” Rehman pushes back against this erasure, forcing audiences to see what remains under the water. The work in The Falls maps the loss of home and the resulting trauma through a national and international system of debt and development, development and displacement. A system that still thrives today.

Residency Workshop

While in residence at Buffalo Arts Studio, Rehman worked with Journey’s End Refugee Services Refugee and Asylee Mentoring Program (RAMP) on a collaborative wall drawing. RAMP serves refugees, asylees, and Special Immigrant Visa holders between the ages of 18 to 24 by pairing them with adult mentors who can best help them achieve their personal, professional, and educational goals. Rehman and workshop participants created stencils based on images that represented community and reflected the broad definition of family. Participants traced and stenciled the shifting images on the wall as a live drawing, exploring how these images communicate, consolidate, and contest ideas about collective and individual identities. The final drawing, titled Journey’s End, includes figurative work layered with symbols and shapes connecting the makers to their own ideas of home.

Artist Biography

Sa’dia Rehman (b. Queens, NY) holds an MFA from The Ohio State University and an MA from The City College, CUNY. Rehman has exhibited at the Wexner Center for the Arts, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Queens Museum, Columbus Museum of Art, The Kitchen, Kentler International Drawing Space, Center for Book Arts, and Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU and Pakistan National Council of the Arts. Rehman was the recipient of the Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson Grant and Meredith Morabito, the Henrietta Mantooth Fellowship and was awarded residencies at Abrons Art Center, Art Omi, Asian American Arts Alliance, Edward Albee Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, NARS Foundation, and AIM Bronx Museum. Rehman’s work has been featured in The Brooklyn Rail, The New York Times, Harper’s, Hyperallergic, ColorLines, and Art Papers.

Exhibition catalog available here.