Date/Time

Date(s) - 02/25/2022 - 04/08/2022

12:00 am

Location

Buffalo Arts Studio

Categories

Opening Reception, Friday February 25, 2022, 5:00-8:00 pm

Part of M&T Bank 4th Friday @ Tri-Main Center

Then and Now

Curatorial essay by Shirley Verrico

Attica NOW is the culmination of CaldodeCultivo’s four-month research residency as part of Buffalo Arts Studio’s Displacement: Reclaiming Place, Space, and Memory exhibition program. Currently based in Buffalo, NY, CaldodeCultivo is a Spanish-Colombian art collective founded by Unai Reglero and Gabriela Córdoba in 2006. CaldodeCultivo addresses conflicts of a global nature that manifest in the local realm. Using different artistic languages, from public installation to video, the collective creates devices of counter-information, agitation, and provocation that work as catalysts for dissent. During their residency, CaldodeCultivo examined the 1971 Attica uprising, which left 43 people dead, almost all of them killed by law enforcement officers retaking the prison.

Attica NOW places the current conditions of prisons and detention centers at the center of its project and identifies incarcerated people, both past and present, as political subjects. All of the still and moving images in the front gallery of Attica NOWcome from the Elizabeth M. Fink Attica Archive. Elizabeth Fink was a human rights lawyer who represented prisoners killed and injured during the 1971 Attica prison uprising. The collection consists of photographs gathered as evidence, trial transcripts, and audiovisual recordings of news coverage, interviews, and documentary footage. The archive also includes materials Fink collected from the Attica Brothers Legal Defense. This content includes photographs and moving images of the prison uprising, guards and officials during the standoff, the subsequent assault and retaking of the prison (“Bloody Monday”) by Russell Oswald and the NY State Police, and the aftermath of the brutal assault. The full collection was acquired as part of the Archive of Human Rights at Duke University and is available digitally in the public domain. All of the documents in the Elizabeth M. Fink Attica Archive have been digitized. For Attica Now, CaldodeCultivo labored to return the photos to analog slides and to present the media through video monitors rather than computer screens.

The gallery is full of antiquated technology that transports visitors back in time. The 21 inch Hantarex MGG video monitor, nicknamed The Block, was popular in public spaces such as nightclubs, chain stores, and airports in the 1980s because multiple units could easily be stacked and stored. The screen fills all but a half inch of casing, allowing multiple monitors to be placed together with minimal space between the images. The video format, including running time codes, points to an era when audiences believed the images they saw and media they were delivered, especially through their television sets on the nightly news. Alongside the monitors, slide projectors hum and click through the slide carousels, recalling both academic and institutional informational and instructional presentations.

Visitors first see Attica NOW in black wall vinyl that is over 100 inches tall. The exhibition begins with scenes from Attica on September 9, 1971 with We are Men, an installation of still text and moving footage projected through analog technologies. Once the inmates of Attica took over the facility, a committee of elected inmates drew up these demands as preconditions to end the takeover and presented them to the public. For Attica NOW, the text of the Declaration to the People of America is a static document stretched across an overhead projector and illuminated on a free-standing screen from the ‘70s. The text is large and only one sentence fits on the screen at a time. Moving the film across the glass platen is not automatic. Some visitors, unfamiliar with this outdated machine, struggle to manage the rolling process. Others stand patiently, turning the crank to read the words written 50 years ago.

Next to the projector, footage from the Elizabeth M. Fink Attica Archive plays on a single Hantarex MGG video monitor. Elliott James “L.D.” Barkley reads the demands for the national news media. The Declaration included calls for better medical treatment, fair visitation rights, improved food quality, religious freedom, higher wages for inmate jobs, and an end to physical abuse. It also asked for basic necessities like toothbrushes and showers every day, professional training, and access to newspapers and books. Additionally, speakers call out “vile and vicious slave masters,” such as the Governor Nelson Rockefeller, New York corrections, and the United States courts, all of whom oppressed these individuals. Visitors also see and hear many of the men speak, each calling for social justice and societal unity. The camera pans across the dozens of black, white, and brown men sitting and standing together in D Yard, some wearing football helmets, others wrapped in blankets, and many with fists raised in the air.

Moving through the installation, the monitors double and then double again. What was a single screen that could be viewed, heard, and understood, multiplies as two monitors with double speakers are stacked atop one another. Here, the chaos begins as Retaking combines news coverage, interviews, and footage recorded outside of Attica on September 13, while State Police and corrections officers prepare to launch their assault. Nearly all of the faces we see on these screens are white. A seemingly endless line of well-armed men in full combat gear stream past the camera. A helicopter flies overhead as military vehicles roll into town. Civilian men and women line the streets, some with cameras pointed at the prison, like they are waiting for a parade. The video jumps between scenes and the sound is muddled as the competing speakers play over each other. The only sound that breaks through the chaos is the rhythmic beating of the helicopter propellers as it flies over the prison wall to drop tear gas on the inhabitants. What followed was the brutal 15 minute assault with almost 2,000 rounds fired into the yard. Next to the video monitors is the projection of two still images where prison officials stand over what remains of the encampment, posing for the camera, with the dead and wounded lying naked behind them.

Snakeline covers four monitors with the violence and torture that was inflicted by prison staff after police and guards regained control. On these monitors, the lines of men, also seemingly endless, are naked with their hands on their unprotected heads. Black and brown bodies are forced to crawl across the yard, through mud and feces, over glass and debris. There are no individual men in the Snakeline footage, only guards and inmates, oppressors and the oppressed. Along with the sound from the four videos, the chaos is amplified as a horn loudspeaker plays the orders from the prison officials that were broadcast across the yard.

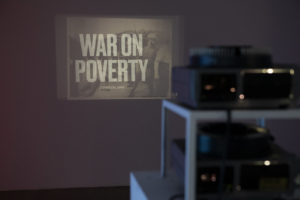

Next to the video monitors is the projection of two still images where prison officials stand over what remains of the encampment, posing for the camera, with the dead and wounded lying naked behind them.Slogans + Massacre is the place in the exhibit where the horrors of 1971 Attica are contextualized as part of an ongoing and intensional system. Slogans + Massacre projects text slides over graphic images of the violence inflicted on the men in Attica, as well as photographs of prison officials posing proudly for the news media. The text slides function as a call-and-response, flashing familiar phrases like “War on Drugs,” as well as counter messages like “War on the Poor.” Both the text and the photo slides progress automatically, however the timers are not synchronized. The words and images are paired differently throughout the exhibition, pointing to the layered complexity inherent in systemic societal problems and the failure of simplistic punitive policies.

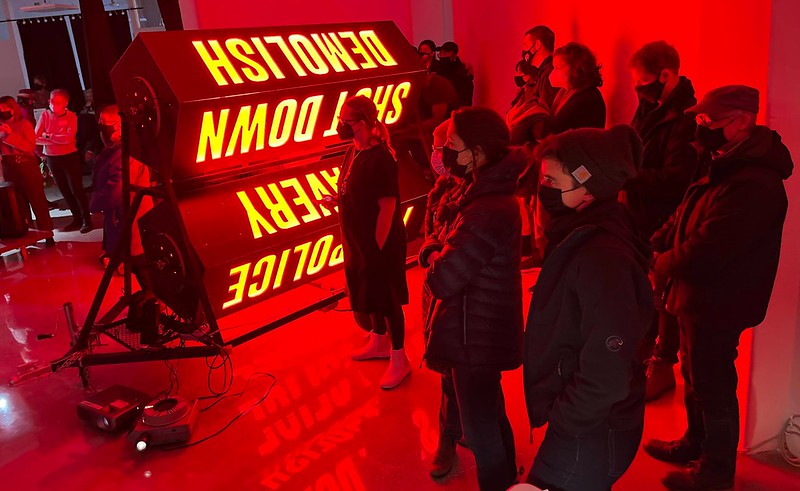

If the front gallery is the “Attica” in the exhibition title, the Joanna Angie Gallery is the “NOW.” ForAttica NOW, CaldodeCultivo designed the Abolitionist Artifact, an activist tool to bring attention to the consequences of the Prison Industrial Complex in the lives of frontline communities. Artifact is defined by Merriam-Webster as a simple object (such as a tool or ornament) showing human workmanship or modification as distinguished from a natural object, especially: an object remaining from a particular period. The Abolitionist Artifact certainly functions as a tool, however its meaning and purpose moves between the past and the present. The artifact employs two rotatable drums, featuring illuminated calls to action on each of the five surfaces. The drums can be rotated and fixed with a simple pin and lock system changing the pairings between upper and lower text.

Like the slide projections, the Abolitionist Artifact physically and conceptually connects the contemporary Prison Industrial Complex to the racism and xenophobia deeply rooted in American history. The Abolitionist Artifactis paired with Niagara Square, an original video filmed in 2022 and combined with still images from the Elizabeth M. Fink Attica Archive. The still images show protestors filling Niagara Square during the 1973 Buffalo trial of indicted inmates known as the “Attica Brothers.” The crowd in these photographs hold signs demanding justice and “Freedom for Attica Brothers Now,” while telling the crowd that “Attica is All of Us.” The activists standing in the snow this past February echo the same sentiments, even 50 years later. In Buffalo, there have been 28 deaths at the Erie County Holding Center since 2005. Nationally, prisoner labor is still exploited and health care of prisoners is still abysmal. The prison system remains a modern-day extension of slavery. Ultimately, Attica NOW serves to collapse the 50 years between the uprising and the current state of incarceration in the US. The exhibition begins and ends with the voices of those most directly impacted by the conditions of prisons and detention centers in our community and they demand better. Attica NOW erases the notion of “progress” while empowering individuals to raise their voices, to do the work, and to make real and lasting change.

Artist Biographies

Unai Reglero is a visual artist, art director, and cultural organizer. His artistic practice has led him to question the role of art in society, always vindicating it as a tool or device capable of impacting its social context. He is completing his MFA in Studio Art at SUNY Buffalo. Gabriela Córdoba Vivas is an artist-scholar that works in the intersection between art, media, and social justice. Her research has revolved around epistemological justice, the right to the city, and cultural representations of transgender sex work. She is a fourth-year PhD student in Media Study at SUNY Buffalo. Together as CaldodeCultivo collective, they have developed projects in several cities in Europe and The Americas. They have been nominated to the Vera List Prize for Art and Politics, NY (2018), and his work is part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of Colombia. Previous CaldodeCultivo projects include: The People’s Coliseum (Cali, Colombia, 2018, Goethe Institut, Museo La Tertulia), Detroiters (Ideas City Detroit – New Museum, 2016); Black Venus Protest (Poland, Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art, 2017), Medellín Sobre Todos (MDE15. Medellín International Art Meeting, 2015), and Comanche (Artecámara. Bogotá, 2015).

Read more about CaldodeCultivo at www.caldodecultivo.com/

This exhibition was made possible, in part, by the generous support of the University at Buffalo Department of Art.

Exhibition catalog available here.