Date/Time

Date(s) - 01/22/2021 - 03/06/2021

11:00 am until 5:00 pm

Location

Buffalo Arts Studio

Categories

Virtual Tour and Artist Talk via Facebook Live

6:00 pm, Friday, January 22, 2021

Part of M&T Fourth Friday @ Tri-Main Center

A Century of History in a Millimeter of Space

Curatorial Essay by Shirley Verrico

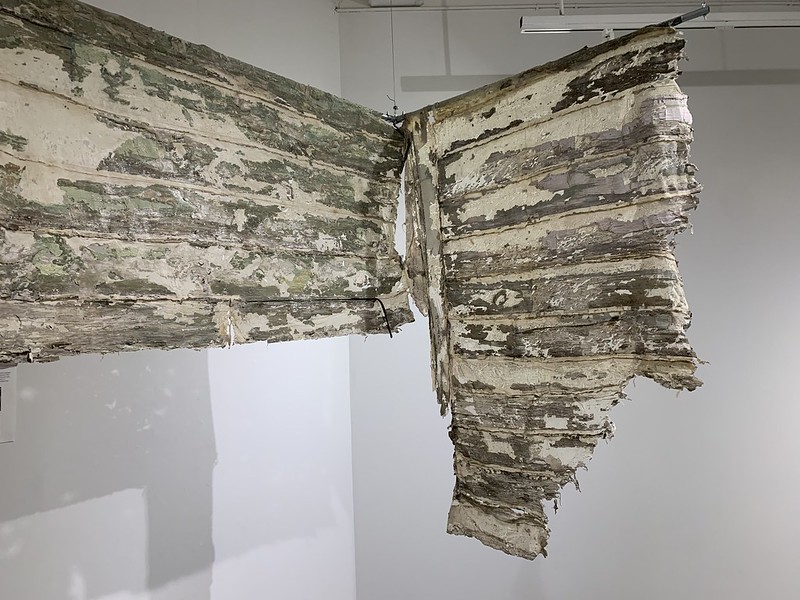

Deindustrialization and disinvestment of the 1970s and ’80s hit Buffalo’s East Side neighborhood especially hard. As Artist-in-Residence at Buffalo Arts Studio, architectural designer Justina Dziama spent the last six months researching the East Side neighborhood that surrounds Tri-Main Center, locating structures that share Buffalo’s story of social and economic distress. Dziama selected factories, churches, and a telescope house that illustrate the intersection of industry, community, and family. Dziama’s artistic practice approaches the various buildings in this neighborhood as sites of material agency in which the surfaces of a structure, exposed to the elements, demonstrate the types of transformations that take place within a community lacking adequate intervention and support. All of the buildings Dziama included exhibit the temporal qualities of neglect and distress. The topography of decaying architecture serves as a metaphor for the cultural and community blight caused by the loss of manufacturing jobs as well as discriminatory economic practices. Her work captures layers of surface deterioration through a series of hyperphysical castings fabricated from latex. The castings vary in color and texture, recalling shrouds or skins, all the while remaining reflective of human scale. The castings hang from steel rods suspended from the ceiling and viewers are encouraged to move around each object, seeing both the sides of each casting. Each object is titled for the structure from which it was made and viewers are invited to “read” each object and recognize the stories embedded in the layers of paint, minerals, and even plant life.

The latex casting process is not unique to Dziama. Swiss artist Heidi Bucher (1926-1993) cast doors, window casings, and rooms in latex and gauze, producing objects she called “skins,” which are part of a larger body of work that reflects her vision of the body as an architectural space and, in turn, of architecture as an extension of the body. Unlike Bucher, who captures and constructs recognizable architectural elements such as doorways and lintels, Dziama captures surfaces, focusing on what is happening to the man made rather than the man made itself. Jorge Otero-Pailos (1971, Spain), who also casts architecture with latex, sees his work as a form of artistic environmental history, visualizing the scale of pollution, especially as it is seen on monumental architecture. Although Dziama’s castings also use the residue on the architecture as a record of history, her work is more interested in the local, recognizing that social, economic and even environmental justice is not distributed equally.  Dziama’s casting process records the almost immeasurable space between the structures themselves and the residue of long-term exposure to industrial air pollution and Buffalo weather. The latex captures and removes the static millimeter of space that recorded the action and inaction of the last century and allows Dziama to bring that record into the gallery space. The casting of Hard Manufacturing (1A,1B), resulted in the most colorful piece in the exhibition, removing multiple layers of paint as well as a significant layer of rust dust from oxidizing materials on the adjacent Buffalo Concrete Accessories property. The deep greens and oranges are spread across the creamy latex like an abstract painting created on brick bond pattern. The casting of the Lovejoy Telescope House at 47 Krupp Street (3A) also removed layers of paint, however in this case, the flecks of pigment stripe the latex like a sort of naturally forming sediment, providing a record of the generations of individuals and families that likely applied the paint themselves.

Dziama’s casting process records the almost immeasurable space between the structures themselves and the residue of long-term exposure to industrial air pollution and Buffalo weather. The latex captures and removes the static millimeter of space that recorded the action and inaction of the last century and allows Dziama to bring that record into the gallery space. The casting of Hard Manufacturing (1A,1B), resulted in the most colorful piece in the exhibition, removing multiple layers of paint as well as a significant layer of rust dust from oxidizing materials on the adjacent Buffalo Concrete Accessories property. The deep greens and oranges are spread across the creamy latex like an abstract painting created on brick bond pattern. The casting of the Lovejoy Telescope House at 47 Krupp Street (3A) also removed layers of paint, however in this case, the flecks of pigment stripe the latex like a sort of naturally forming sediment, providing a record of the generations of individuals and families that likely applied the paint themselves.  History is literally embedded in the limestone that makes up the foundation wall of St. Ann’s (5A). The aggregate concrete used to form the foundation wall includes concrete, stones, and even fossils, some of which adhered to the latex during casting. Copper oxide, the result of decades of atmospheric corrosion, also marks the cast along with mosses and lichens growing in the small pockets of moisture created by the corrosion. The cast of Iroquois Brewery (5A) was made along one of the bricked-in windows. The casting includes a reverse-shadow of sorts where a conduit pipe protected a small area from the elements. The shape of the pipe appears in reverse on the casting, free of much of the organic and inorganic material that adhered to the bricks. Attached to this cast are some of the small plants that were growing in the spalling bricks; the result of the physical freeze-thaw cycle that creates cracks in which seeds and spores find a home.

History is literally embedded in the limestone that makes up the foundation wall of St. Ann’s (5A). The aggregate concrete used to form the foundation wall includes concrete, stones, and even fossils, some of which adhered to the latex during casting. Copper oxide, the result of decades of atmospheric corrosion, also marks the cast along with mosses and lichens growing in the small pockets of moisture created by the corrosion. The cast of Iroquois Brewery (5A) was made along one of the bricked-in windows. The casting includes a reverse-shadow of sorts where a conduit pipe protected a small area from the elements. The shape of the pipe appears in reverse on the casting, free of much of the organic and inorganic material that adhered to the bricks. Attached to this cast are some of the small plants that were growing in the spalling bricks; the result of the physical freeze-thaw cycle that creates cracks in which seeds and spores find a home.  Dziama recognizes that the casts can be viewed as shrouds, suggesting an end or even death. The artist would prefer, however, that viewers see the casts as palimpsests instead, bearing the physical traces of continuously changing social, environmental, and economic conditions of a neighborhood. She notes that the word “palimpsest” comes from the Latin palimpsestus, which derives from the Ancient Greek palímpsēstos, (again scraped), a compound word that literally means “scraped clean and ready to be used again.” The castings are meant to show viewers both the history of these buildings as well as the beauty that remains. By doing so, she hopes the community will be inspired to reimagine this neighborhood and see that it, too, is beautiful and that it is time for the East Side to share in the story of Buffalo’s re-birth.

Dziama recognizes that the casts can be viewed as shrouds, suggesting an end or even death. The artist would prefer, however, that viewers see the casts as palimpsests instead, bearing the physical traces of continuously changing social, environmental, and economic conditions of a neighborhood. She notes that the word “palimpsest” comes from the Latin palimpsestus, which derives from the Ancient Greek palímpsēstos, (again scraped), a compound word that literally means “scraped clean and ready to be used again.” The castings are meant to show viewers both the history of these buildings as well as the beauty that remains. By doing so, she hopes the community will be inspired to reimagine this neighborhood and see that it, too, is beautiful and that it is time for the East Side to share in the story of Buffalo’s re-birth.

Rewriting Buffalo

Post Curatorial Essay by Stephanie Wong-You

A Millimeter of Space is a history of Buffalo, written between the lines of what artist and architectural designer Justina Dziama references as palimpsests. The exhibition tells the story of the people of Buffalo, those that came and went, in the casting gently peeled from the Lovejoy Telescope House at 47 Krupp St (3A), an object that literally reveals layers of paint applied by each family that resided there. In the ten latex castings hanging in the Buffalo Arts Studio gallery, I read the diverging story of those that came, and those that stayed behind. I read the story of the redlining of East Side African-Americans in those layers, when the development of highways and subsidized mortgages facilitated predominantly white Americans to seek homeownership in the suburbs, leaving the city. While at the same time, racial covenants were embedded into the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, segregating African-Americans to specific areas of the city, and curtailing African-American purchasing power as risky investments, and the depressing of African-American owned home values. The impact of these policies still exists, as does the consequences of still inhabited neighborhoods given up as blight. Dziama tells the story of when manufacturing jobs left for the American South [Houdaille Industries 2A, 2B, 2C] for lower labor costs and anti-union environments. Between the lines, I read that at its peak, around 35% of Americans were in unions in the 1950s. Eventually, other manufacturers also departed for the Global South for ever cheaper labor; leaving behind the spectre of a once robust organized labor class, and the ongoing struggle for dignity, living wages, and labor protections across the world. As Buffalo is in its transformational moment of resurgence, grappling with development and generational disinvestment, the center of this community redevelopment should be the people who have been here through Buffalo’s downturns and held on. To whom is housing, employment, public space, preservation, renewal created for? As the city welcomes large scale development projects, and older generation residents see rising housing and living costs, what does revitalization look like for the historically marginalized, those erased from large scale development conversations? What is being done, at the forefront of community development considerations to disrupt and change the pathway of inequitable practices? These, I believe, are the lingering questions that emerge from Dziama’s conversation. I see community development practitioners answering these questions and writing Buffalo’s future. From Grassroots Gardens, a network of community spaces where the public can find refuge and reconnect with nature to the FB Community Land Trust, which has met community unease and concern for the future affordability of housing in the face of development, with homes for native Fruit Belt residents. From, Westminster Economic Development Initiative (WEDI), which supports pathways to community wealth building and works to close the wealth gap for refugees, native BIPOC, and the working class through accessible loans and financial education. To coalitions like the Buffalo Niagara Community Reinvestment Coalition, a group of 13 local organizations working to eliminate inequality and discriminatory practices within financial institutions of Western New York, and advocates for community benefits and equitable economic frameworks, including Community Development Financial Institutions and Public Banking to co-create more just and prosperous communities. People centered and community directed development, which acknowledges our full history, is what we must work for to reconcile our relationships and patterned inequality, to co-create a more resilient, inclusive, and fully realized Buffalo.

To read more about discriminatory economic practices, redlining, and segregation in Buffalo, see the following reports:

Erasing Red Lines: Part 1- Geographies of Discrimination by Russell Weaver

A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo by Anna Blatto

Governor Cuomo Announces Findings of New York Investigation of Redlining in Buffalo (https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-findings-new-york-investigation-redlining-buffalo)

About the Author Stephanie Wong-You is an Economic Development Program Associate at Westminster Economic Development Initiative (WEDI) and has worked with community based organizations for ten years spanning disability rights, small business, and neighborhood building through community organizing, financial education, literacy initiatives, and language access.

This exhibition is funded in part by The National Endowment for the Arts.

Exhibition catalog available here.

Post-Curatorial Essay available here.